Imagine a beautiful future, abundant in life and wealth, where no one is lacking. New technologies spring from industrious people, and everyone has gratifying work with decent pay. The goods and services produced marry a love of craft with a broad desire to improve people’s lives. People live balanced, healthy lives connected to their communities. Everyone has time to travel and pursue interests outside of work while maintaining healthy finances. Diseases become scarce as people regularly share nutrient-dense food with loved ones. Cities are centers of commerce and recreation, with lush parks, clean streets, clean water, and clean air.

This is the future that capitalism portended at its founding. We are halfway there; the “invisible hand” of Adam Smith has extended life expectancy, produced innovative technology, and given people opportunities for upward mobility. At the same time, it has decreased the quality of life, produced endless meaningless and wasteful products, and deteriorated cultural values. Worst of all, late-stage capitalism threatens to destroy our planet.

The earth produces enough raw material to go around. Our economy produces enough money for everyone to live a comfortable and safe life. Somewhere in the process of turning nature into a capital-generating machine, we encounter a distribution problem. People hold onto wealth; money stays where it’s made. Our system favors rich people and makes them more rich. Those behemoths then maintain market share by decreasing the quality of their products and services and exploiting labor. We may act like this is an unfavorable accident, but it keeps happening.

How can we prevent capitalism from plundering our most valuable resources, corrupting our values, producing waste, and exploiting the poor?

Here are a few bulleted items that I will expand upon to make capitalism’s successes work for all in the long term:

Contextualize economy as a shared, limited space and not as an infinite game to win

Set limits that prevent monopolies and promote ecological health

Adjust how tax is distributed toward public projects and who carries out public projects

These, I hope, will help close the disturbing gap between our ethical values and the market value of goods and services.

Contextualizing Economy

Picture the world in a pre-human state. It’s a system of life that we would call resources. When we arrived on the scene, we decided how valuable everything was, including human labor. The value of these things fluctuates, but the fact remains that everything we produce—from skyscrapers to chemical substrates in beauty products to fiber optic cables to the screens that produce LED images—comes from the earth. As we rearranged the natural physical world around us, we created money to ensure fair exchange of goods and labor. Money serves three purposes: store of value, medium of exchange, and unit of account. Though we often confuse money with wealth and wealth with the economy, the economy is simply the goods and services we produce and the materials necessary for production. If we view the economy not as something separate from nature but as what we choose to do with the raw material that is nature, then we can adopt a better frame of reference with which to view our productive endeavors.

This is where sustainability comes in. Sustainability often comes across as a buzzy new-age school of thought, but it should be seen as the perspective that allows us to function properly in our human role of resource management. Sustainability is important because 1) it’s healthy for all living beings, and 2) it ensures the future of our economy. The closer we get to a truly sustainable interaction with our environment, the more those two points converge, and our collective well-being becomes our economy.

Until then, producing, manufacturing, distributing, and selling products takes a toll on humans and the surrounding environment. Cargill is an interesting case, because its stated purpose is to “nourish the world.” Cargill is the largest agricultural company and the largest privately held company in the US, with annual revenue of $165 Billion. It is the second largest soy exporter in Brazil, where its production lines are responsible for catastrophic deforestation in the Amazon. Although Cargill publicly reformed its policies in response to clamor over its environmental impact, reports show that Cargill’s reformed accounting is grossly misleading and inaccurate.

Capitalism’s consistently negative effects on the environment are compounded by its mistreatment of workers, especially those in the lowest-paying jobs at large multinational corporations. Apple is one of the largest companies in the world and is responsible for our current vision of the future. Buying its products and its scaffoldless digital architecture means voting for its business practices (typed from a 2021 MacBook Pro). Apple uses a Chinese company called Foxconn to assemble its products. In 2010, 18 workers at Foxconn’s flagship factory attempted suicide by jumping from the dorm buildings where they lived in the factory complex. Fourteen of these attempts were successful, and “20 more workers were talked down” from jumping. A Guardian article from 2017 gives Apple’s response to the situation, which is reminiscent of Cargill’s ineffective reforms. Reforms include nets installed to catch falling bodies, counselors hired by Foxconn, and a pledge not to attempt suicide that all workers had to sign. As Steve Jobs said when reports of these 2010 suicides broke: “We’re all over that.” However, a worker interviewed in the 2017 Guardian article stated that nothing has changed: “It’s not a good place for human beings…there is no improvement since the media coverage…every year people kill themselves. They take it as a normal thing.”

Unfortunately, the reason America is so wealthy is the same reason we are responsible for these problems. These companies are too big. They believe that if they can sell us convenience at a low enough cost and if their misdeeds are far enough away that their coverage may never reach America or ever be reported, then their stock price can continue to climb.

Business on this global scale is not sustainable. We have to be tougher on monopolies. The cost of production is truly catastrophic, and the impact on the consumer is manipulative, unhealthy, and even corrosive. I’ll admit that I’m as addicted to these products as anybody. But addiction is a disease, and in this case, its cause is the monopolistic tendencies of late-stage capitalism.

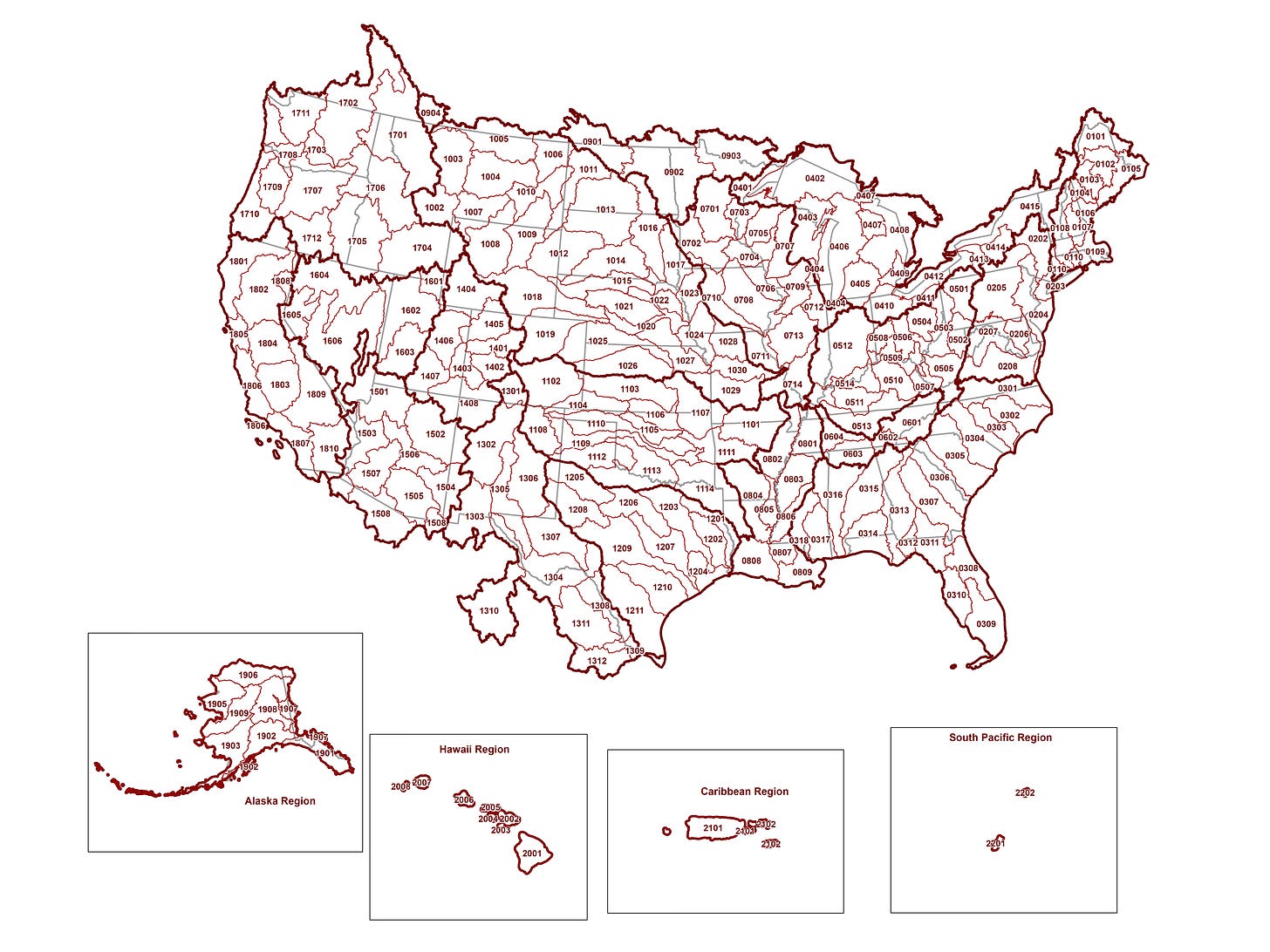

If we safeguard for public health first, we can prevent this from happening. Years ago, I wrote (recorded) (it’s kind of embarrassing) about this concept with an idea that I thought was wholly original. It turns out John Wesley Powell proposed it in an 1878 Report on the Lands of the Arid Regions of the United States. Powell was the second head of the U.S. Geological Survey and testified to the Senate that the undrawn boundaries for new Western land should follow the lines of watershed boundaries. The idea is that when land is divided up into arbitrary lines, people have no incentive to treat their land as part of a larger ecosystem. Individuals with a square of land up the mountain may make a living off of deforesting their land, while individuals who own the mouth of the river effectively own the commerce and fertile land that is part of a larger system. Treating these two plots of land as disconnected encourages reaping them for the disadvantage of the larger system and for the disadvantage of the people who thrive on the health of the system.

Powell proposed this idea for a water-scarce, uncolonized area, but it would benefit us to adopt these political boundaries for the entire United States. Because we mismanage water through the exploitative means of massive corporations, our extremely wealthy country is in a water crisis. Texas Department of Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller reported on the dire water deficit that Texas is experiencing due to mismanagement. Cities in Texas lose up to 30% of water before it reaches the customer. Texas’ sugar production, 6,000 acres of citrus, and four of its five vegetable crops have dried up due to lack of water. Commissioner Miller goes on to say that rising food costs are largely due to added freight from shipping food from Mexico and elsewhere. The problem is obviously bigger than Texas; although America used to be the world’s largest food exporter, it bought $16 billion more food than it exported in 2023. This year, we are forecast to double that number, importing $32 billion in food.

As Commissioner Miller describes, the problem is not that we aren’t getting enough rain. The problem is our approach to our resources. We let rainfall run through sewage systems rather than capturing it off of rooftops. During high water events, water that we could capture in off-channel storage flows right by us. The money for these projects is already budgeted, but we’re not using it.

What do these water problems have to do with capitalism? Once again, money is just a means of exchange based on natural resources. If we change how we perceive and interact with our fundamental resources, we can build more equitable means of commerce. If we account for the health of our communities and ecosystems first, then we, by proxy, disallow corporations from becoming the leeching ecosystems that we depend upon.

With these watershed boundaries in place, we can better account for natural resources. No watershed state should be allowed to pull water or energy from another state, except in extreme cases of need. This is another way to regulate how we use water in food production, infrastructure management, and manufacturing. The result will increase the lives of businesses and people through the health of our natural economy.

Setting Limits that Prevent Monopolies

Rather than one central bank from which all other banks secure funds, each of these watershed states should have its own central bank. Just as rainfall fluctuates from year to year but generally will produce a predictable amount in a watershed boundary, so will these smaller central banks serve as the reserves from which an area can secure loans and build up the progress of the region. Decentralizing power in this country will give us greater understanding of regional issues and allow us to adjust to localized problems more efficiently. The demand for one region will not be the same as another, and each region needs to find its own equilibrium in order to build a stronger union.

Setting these water limits could also benefit the nutritious quality of food. Governments could set the proper limits on how much “market share” of a given crop each watershed could produce. That way we can address industrial agriculture and prevent one region from producing an excess of corn that results in a litany of unhealthy corn-based products.

Currently, our nation produces food through large industrial factory farms. These farms operate on monocultures, industrial equipment, herbicides, and pesticides. In other words, these farms try to produce as much as possible of one crop (often corn or soybeans), plant and harvest that crop through massive highly specialized machines, and chemically nuke anything that might threaten that crop. Soil that produces diverse crops is richer, more resilient, and more productive. There is a metaphor here. If we diversify our crop, it will produce more abundant and more nutritious food for longer. The same goes for our workforce and businesses.

These watershed boundaries give an accurate idea of how much growth and life we can depend on from a specific region. The agricultural output of one of these regions should serve to feed that region, except in times of extreme drought or in the production of foods that cannot be grown in the other areas.

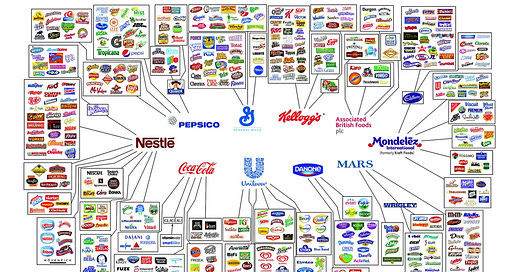

Businesses should not be so big, and neither should farms. Producing nutrient-dense food specific to each region would be beneficial in a number of ways. It would bust up the ten corporations depicted above that control almost all food and beverage. It would diversify the companies in control of food production. It would prevent businesses from overspecializing in food production and building food from chemical substrates rather than relying on nutrient-dense ingredients. Relying on nutrient-dense ingredients is complex—it requires humans to do much of the work, instead of machines. This would increase labor costs, but it would also increase jobs. The increasing labor costs could also be offset by cutting out all of the middlemen in distribution and all of the industrial infrastructure.

Making every grocery store product in the same area as the place it’s sold also brings produce to food deserts. Providing this healthy food in every neighborhood would make people more resilient to disease. It would also make the land more resilient to disease. Relying on herbicides and pesticides produces superbugs immune to the catastrophic chemicals introduced to our bodies and food. If instead you build up resilience from within the system, then those bugs are biologically addressed without creating a strain that is more malignant and harder to kill. When humans eat this nutrient-dense food, we see chronic diseases decrease and quality of life increase. Killing factory farms would also greatly decrease the likelihood of pandemics, as we saw that COVID occurred due to unsafe agricultural practices in China. We can expect medical issues to drop off if people are eating real food and toxic snacks from Pepsico are phased out.

Building a solid backbone of resource management and fairly compensated, skilled labor will move us from an exploitative economy to a regenerative one. This shift in perspective involves building equity from the ground up rather than from the top down, which seems appropriate because, after all, that’s how resources grow.

Using these watershed boundaries as political boundaries will allow us to delineate the limits of what resources corporations can draw upon. If a corporation cannot use resources outside of its own watershed boundaries to source, manufacture, and distribute its product, then that product can be considered unsustainable. There are multiple ways to encourage sustainable and equitable production through these boundaries. At the far end of things, governments could prevent corporations from using any resources, including labor, outside of their watershed boundaries. That may seem like an extreme measure, but I believe that working towards that future would create a sense of regionality that we have lost since the “good old days” of American history when every place didn’t look like a Walmart parking lot (because every place is only so far from ubiquitous overreaching corporations like Walmart). To that end, franchises could be disallowed outside of watershed boundaries.

A less stringent regulation would be to heavily tax businesses by the extra-watershed resources they use. Regardless, if businesses are not prevented from outsourcing labor or other resources, they should at least be penalized for doing so, as all this allows is unfair compensation and environmental destruction. Shortening the reach of companies allows for greater competition and close-to-home observation of the actual impact of a business. It also allows for more and diverse companies to serve regional needs. The commodification of our lives has produced a bland and uninteresting built environment, and encouraging the growth of small business will bring back the detailed cornices that big business cuts when they are looking for larger margins.

The unpopulated regions that we draw upon are not there for us to deplete, they are the land of future generations, and we have to treat it as such. The price of goods cannot be dictated by how low the bottom line can go. Businesses that cannot pay their workers fair wages or manufacture without burning out ecosystems do not have tenable products. The businesses that we cull out of the marketplace by implementing these restrictions are ones that were a leech on public health anyway. People with a higher sense of ethical values and greater innovation will fill the void with win-win solutions.

As the idea relates to corporations, a lot of details need to be worked out, but there are a lot of benefits of encouraging local sourcing and manufacturing. Some of these benefits include cutting middlemen, increasing jobs, raising wages, increasing biodiversity in nature and in design, and gauging environmental impact through real-time observation.

This watershed principle could also prevent corruption in other industries. Consider the entertainment industry. The scandals around figures like Harvey Weinstein and P. Diddy elucidate how manipulative people in the industry will be when power is consolidated into a few enormous studios. Most people taking their music or acting careers seriously move to Los Angeles or New York because that’s where most of the major studios are. If studios couldn’t have more than, say, 10% of market share, which is still a lot, and one watershed boundary couldn’t have over 30% of market share, then creatives looking for work would have more opportunities.

This initiative would even out the population distribution in the US and would decrease the strain on certain areas that currently support excessively large cities. I have written in the past about Los Angeles and Los Vegas water issues, and the fact that these cities and possibly many others would have to decrease in size if we were to ensure their longevity. The idea is that these watershed boundaries could even out where corporations have become monopolies, cities have become resource drains, capitalism has increased inequality beyond the pale, and energy is scarce.

Many policy decisions could help with this transition and help money flow more naturally. It is important to note that these decisions simply guide money like a river bank and prevent us from depending on things like massive corporate layoffs that are part of the cycle of prodigiously large multinational corporations.

Public Funds and CEO Pay

People are more willing to pay taxes if they see that they are going to productive ends. One idea is that instead of giving your taxes to the government, you donate that calculated tax dollar amount to certain government-approved, privately owned trusts. Those trusts could be “mental health services” or “roadways” or “parks and rec” or “high schools” or “social security.” The accounting for those trusts should be completely transparent and publicly available on a website. That way people can see how much money is in a certain trust and what that trust can then afford in the coming years. Perhaps there is a meter that shows the “roadways” trust is only on budget to fix 50% of the roads currently in disrepair. People can then “donate” their taxes to this trust if they find it motivating, and the website would be updated in real-time and show others who still have tax money to donate before the deadline where other trusts stand as well.

This is a truly capitalist form of taxation that 1) encourages people to actually pay their taxes instead of evading them, 2) have a stake in their communities, and 3) shift their relationship with money by encouraging generosity. Private nonprofits instead of government agencies can then deal with the funds in these tax trusts. We all know that the private sector gets work done better than the public sector. These nonprofits can continue to gather donations, as they do year-round, and serve projects that uplift the oppressed and are generally for the common good. The government will save money by outsourcing the work to the private sector. That saved money can go towards improving health care, the deficit, lowering the cost of public universities, or other good uses.

Final Thoughts

I have much more to research about watershed boundaries and the flow of money, but I will leave it there for now. The way that idea relates to corporations can be adjusted in a lot of ways, but there’s something there. It is interesting to consider the life of a product and what businesses couldn’t exist under this principle. Could Nvidia make its chips with constricted sourcing? Maybe not, as mineral sources are rarer than most others. However, are we so sure that the impossible amounts of wealth Nvidia is generating won’t come crashing in when AI becomes an unsustainable energy drain, or it threatens our quality of life to an alarming degree? Perhaps the proper limits would prevent things like these from happening, and bad bets we made along the way have to be selected out. It’s only rock and roll.

Mark Carney writes in Value(s) that “value in the market is increasingly determining the values of society” (p. 12). He attempts to “draw out the consequences of the convenient shorthand of price equalling value” by giving corporate leaders a five-hundred-page talking-to (p. 16). It reminds me of Adam Smith’s belief that if society is set up correctly, people pursuing individual pursuits will provide for others’ happiness. That is true if people and their desires are set up correctly. But people can’t resist a cheap thrill, and when they make money, they aren’t generous. So the “invisible hand” that’s meant to drive progress forward ends up serving the desires of those with the strongest will, and we end up living in a world of tyrants with good marketing. As much as people may hate it, we need the right regulations. I suggest we use the regulations nature already gave us.

In the youth of this nation, two founding fathers fought for the vision of their great American project. As Alan Greenspan writes in Capitalism in America: “Hamilton wanted America to become a commercial republic powered by manufacturing, trade, and cities. Jefferson wanted it to remain a decentralized agrarian republic of yeomen farmers” (p. 62). Hamilton obviously won, but after 200 years of his counsel, I think he would appreciate a middle ground that tempers the exagerrated problems of his vision. By decentralizing banking and maintaining ecological equity, we can bolster manufacturing and make our cities more efficient.

I don’t necessarily think things are headed in the right direction, and I think setting the proper environmental restrictions will allow us to be creative in truly productive ways that actually drive society forward. It might produce a shockwave through the markets. But I argue that it is better to face that difficulty head-on and undergo that transition willingly than to let these businesses grapple for larger and larger market share until the catastrophe reaches us suddenly through environmental disrepair or social unrest. If we do it smoothly, we can transition from a monochromatic culture dominated by big fish who stay alive at the expense of their employees and customers to regional enterprises that flourish off of biological life and diverse schools of thought.